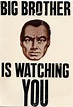

Evolution of the Surveillance State

Behind Winston’s back the voice from the telescreen was still babbling away about pig-iron and the overfulfilment of the Ninth Three-Year Plan. The telescreen received and transmitted simultaneously. Any sound that Winston made, above the level of a very low whisper, would be picked up by it, moreover, so long as he remained within the field of vision which the metal plaque commanded, he could be seen as well as heard. There was of course no way of knowing whether you were being watched at any given moment. How often, or on what system, the Thought Police plugged in on any individual wire was guesswork. It was even conceivable that they watched everybody all the time. But at any rate they could plug in your wire whenever they wanted to. You had to live — did live, from habit that became instinct — in the assumption that every sound you made was overheard, and, except in darkness, every movement scrutinized.

George Orwell, 1984, Secker & Warburg, London, 1948, Print

In 1948 George Orwell envisioned a future unsettling to the current reality of endless war, 24-hour news/propaganda cycle, and pervasive surveillance to control behavior and potential threats. A generation of Americans after World War II, with memories of the Gestapo still stirring and seeing the growth of oppressive regimes in Eastern Europe, the Soviet Union and Asia took a cautionary message from it.

Now it is thirty years beyond the title date and the technology of surveillance has finally caught up to Orwell’s vision, and surpassed it. Yet the generation born half a century after his book’s publication, in the shadow of the Internet, seems unconcerned with its reach. This paper will try to answer, “Should they be?”

I write this on a laptop personal computer, unheard of in 1984, let alone in 1948. Yet its flat screen, speakers and camera eye, capable of being turned on remotely, are every much the “telescreen” of Orwell’s imagination.

What Orwell did not anticipate was how his “telescreen” would be miniaturized. Now a hand-held device with power and mobility he could not have imagined, it is something people have learned to love for taking and sharing pictures and videos and sharing thoughts. You can also make telephone calls with it, send and receive emails and texts, surf the Internet, play games, do banking, watch movies, news and other content, download music and books, make purchases, have your movements tracked by satellite, use the services of over 1000 apps, in short, stellar performances for Big Brother.

No longer a cop on every corner as Allan Pinkerton envisioned (Secrest), but the ability to run Facebook photos through facial recognition software and gait-pattern logarithms used on Tweet shares and surveillance cameras to catch the bad guys (Shaogang, et al). Just a taste of ways developed that have made our lives an open book, ready or not.

Two world wars, a Cold War, a War on Drugs and the events of September 11, 2001 have conspired to build the tools necessary to oversee more than a decade-long “war on terrorism”, militarizing our society in an increasingly unsettled world. The public’s fear has been orchestrated to allow a burgeoning security industry after intelligence agencies were roundly criticized by the mass media for the lack of Middle East intelligence that allowed 9/11 to happen. NSA and an alphabet of other agencies now have the technical and legal tools capable of unprecedented intrusions in to the lives of people around the world.

Surveillance is probably the oldest of the investigative techniques, maybe dating to the first time someone eavesdropped on a conversation. This paper will look at surveillance and its use as a law enforcement tool; a story that highlights massive technological advancement and many blurred lines. It is closely tied to the history of the development of the uniformed police and of the dance between public acceptance of overt and covert forms of “preventive policing”, which demands the most aggressive surveillance strategies. But lines blur when there is no longer an “expectation of privacy,” given the porousness of cyberspace.

One more, and counting.

LikeLike